| 25 | Ways to Apply Functions |

When you write f[x] it means “apply the function f to x”. An alternative way to write the same thing in the Wolfram Language is f@x.

f@x is the same as f[x]:

In[1]:=

Out[1]=

It’s often convenient to write out chains of functions using @:

In[2]:=

Out[2]=

Avoiding the brackets can make code easier to type, and read:

In[3]:=

Out[3]=

There’s a third way to write f[x] in the Wolfram Language: as an “afterthought”, in the form x//f.

Apply f “as an afterthought” to x:

In[4]:=

Out[4]=

You can have a sequence of “afterthoughts”:

In[5]:=

Out[5]=

In[6]:=

Out[6]=

Apply numerical evaluation “as an afterthought”:

In[7]:=

Out[7]=

In working with the Wolfram Language, a powerful notation that one ends up using all the time is /@, which means “apply to each element”.

Apply f to each element in a list:

In[8]:=

Out[8]=

f usually would just get applied to the whole list:

In[9]:=

Out[9]=

Framed is a function that displays a frame around something.

Display x framed:

In[10]:=

Out[10]=

Applying Framed to a list just puts a frame around the whole list.

Apply Framed to a whole list:

In[11]:=

Out[11]=

@ does exactly the same thing:

In[12]:=

Out[12]=

In[13]:=

Out[13]=

The same thing works with any other function. For example, apply the function Hue separately to each number in a list.

In[14]:=

Out[14]=

Here’s what the /@ is doing:

In[15]:=

Out[15]=

It’s the same story with Range, though now the output is a list of lists.

In[16]:=

Out[16]=

Here’s the equivalent, all written out:

In[17]:=

Out[17]=

Given a list of lists, /@ is what one needs to do an operation separately to each sublist.

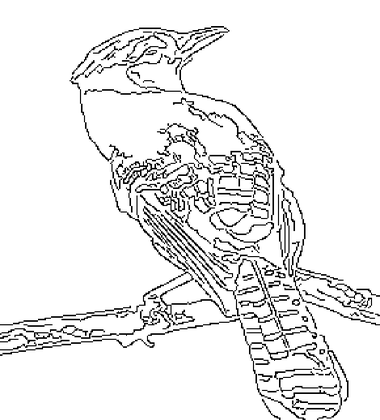

Apply PieChart separately to each list in a list of lists:

In[18]:=

Out[18]=

Apply Length to each element, getting the length of each sublist:

In[19]:=

Out[19]=

Applying Length to the whole list just gives the total number of sublists:

In[20]:=

Out[20]=

Apply Reverse to each element, getting three different reversed lists:

In[21]:=

Out[21]=

Apply Reverse to the whole list, reversing its elements:

In[22]:=

Out[22]=

As always, the form with brackets is exactly equivalent:

In[23]:=

Out[23]=

Some calculational functions are listable, which means they automatically apply themselves to elements in a list.

In[24]:=

Out[24]=

The same is true with Prime:

In[25]:=

Out[25]=

A function like Graphics definitely isn’t listable.

This makes a single graphic with three objects in it:

In[26]:=

Out[26]=

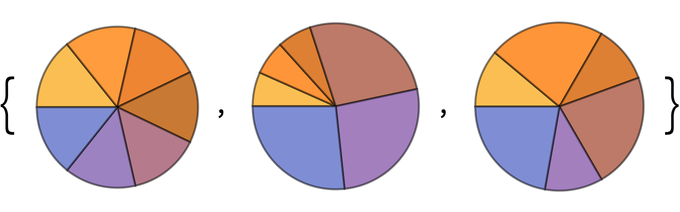

This gives three separate graphics, with Graphics applied to each object:

In[27]:=

Out[27]=

When you enter f/@{1, 2, 3}, the Wolfram Language interprets it as Map[f, {1, 2, 3}]. f/@x is usually read as “map f over x”.

The internal interpretation of f/@{1, 2, 3}:

In[28]:=

Out[28]=

| f@x | equivalent to f[x] | |

| x//f | equivalent to f[x] | |

| f/@{a,b,c} | apply f separately to each element of the list | |

| Map[ f,{a,b,c}] | alternative form of /@ | |

| Framed[expr] | put a frame around something |

25.4Make a list of letters of the alphabet, with a frame around each one. »

25.5Color negate an image of each planet, giving a list of the results. »

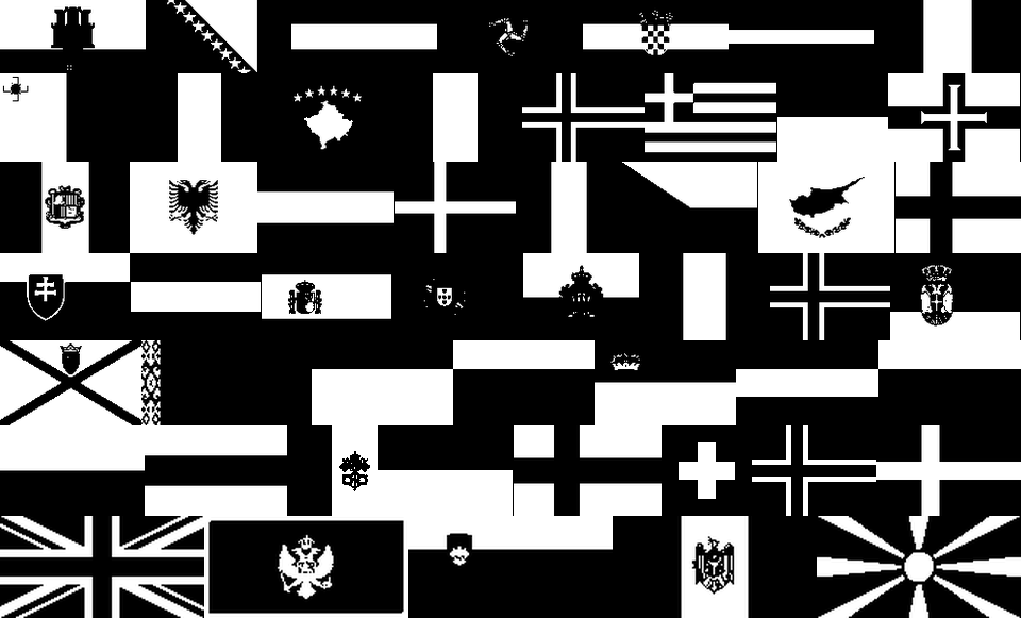

25.7Binarize each flag in Europe, and make an image collage of the result. »

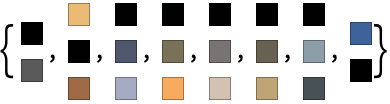

25.8Find a list of the dominant colors in images of the planets, putting the results for each planet in a column. »

25.9Find the total of the letter numbers given by LetterNumber for the letters in the word “wolfram”. »

Why not always use f@x instead of f[x]?

f@x is a fine equivalent to f[x], but the equivalent of f[1+1] is f@(1+1), and in that case, f[1+1] is shorter and easier to understand.

It comes from math. Given a set {1, 2, 3}, f/@{1, 2, 3} can be thought of as mapping of this set to another one.

Typically “slash slash” and “slash at”.

It’s determined by the precedence or binding of different operators. @ binds tighter than +, so f@1+1 means f[1]+1 not f@(1+1)or f[1+1]. // binds looser than +, so 1/2+1/3//N means (1/2+1/3)//N. In a notebook you can find how things are grouped by repeatedly clicking on your input, and seeing how the selection expands.